Introduction

Building on Cronin and Kramer’s (2018: 84) hopeful suggestion that:‘…the repetition of certain kinds of images creates an iconography of oppression when it comes to the treatment of animals in our contemporary society. Artistic interventions have the potential to interrupt this system.’ (My emphasis), The following research question has been formulated for this project:

How can Visual Utopian Experimentation be developed as an artistic research methodology that defamiliarises violent discourse in the present; fabricates alternative perspectives, and engenders ‘that which does not yet exist’ for nonhuman justice, particularly for ‘farmed animals’ in biocapitalism?

Industrialized animal farming under biocapitalism reflects a deeply entrenched system of normalized, large-scale violence in human-animal relations (Cudworth, 2015). The scale is immense. According to UN estimates, 66 billion chickens are killed annually, compared to 1.5 billion pigs and 300 million cattle. At any one time, around 23 billion chickens exist worldwide—three for every person—making them the most numerous bird species by far (Ritchie & Roser, 2017; Bennett et al., 2018). The vast majority of these animals are bred and slaughtered in industrial facilities that are sites of relentless suffering and unnecessary cruelty (Hunnicutt, 2019). Ethical concerns over this system are increasingly joined by arguments related to environmental damage and human health risks (Carrington, 2019; Heidemann et al., 2020). A third of the world’s crops go to feeding farmed animals; nearly 80% of agricultural land supports their feed production, and grazing occupies a quarter of the Earth’s ice-free land surface (Bennett et al., 2018). As global populations grow and demand for animal products rises, this system significantly drives overlapping ecological crises—from biodiversity loss and habitat destruction to greenhouse gas emissions (Reynolds, 2013). At the same time, high consumption of processed meat is strongly associated with serious health issues, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes (Bouvard et al., 2015).

While critical animal studies writers raise the violent nature of the human-farmed animal relationship, at the same time many philosophers and environmentalists argue that the disaster of climate change and species extinction is founded in modernism, global capitalism and humanism; particularly human exceptionalism and the dualism that pervades these organisational systems and is entrenched in the nature-culture hierarchical divide (with culture always perceived as superior to nature and power always residing in the human). These writers suggest we recognise entanglement of human-more than human relationships and an ethics of care toward ‘other’ nature (Harraway, Braidotti, Barad, Moore). Most strangely, to me, these writers largely ignore the all pervasive violence to the farmed nonhuman, as if the farmed nonhuman, and industrial farming practices, were separate from, rather than central to the ecological crisis and human destruction of ‘other ‘nature’.

Public awareness of these interlinked problems is growing only slowly, but beginning to prompt broader cultural and political critiques of what is termed “meat culture”—the norms, values, media, habits, and culinary preferences that shape shared attitudes toward meat (Potts, 2016). This shift coincides with growing interest in plant-based diets and lifestyles. Still, such alternatives remain marginal, particularly in light of increasing global meat consumption—especially of processed products (Godfray et al., 2018). Transforming the current animal agriculture system is essential for ethical, environmental, and health reasons as well as if the human exceptionalist paradigm is to be challenged. Thus questions of how we build momentum for that change and what role the Arts play, is crucial. How can we address the deeply embedded social and cultural systems that normalize meat production and consumption? What creative, cultural, and imaginative artistic strategies might complement traditional advocacy?

While exposing the routine violence inflicted on animals can be a powerful tactic in animal rights campaigns, such strategies are limited in their standalone impact (Adams, 2021). Therefore, it is essential to explore other ways of engaging audiences and promoting alternatives. This thesis suggests the method of visual utopian experimentation, which builds on work in the visual arts on futurity, including ‘Radical futurisms’ (Demos, 2024) and Fictioning (Burrows and O’Sullivan, 2018?) amongst others. It extends this Artistic method, by adding a Utopian method borrowed from the Social Sciences that proposes ‘cognitive estrangement’ (Suvin, date), itself directly developed from Bertold Brecht’s notion of ‘alienation’, as a way to defamiliarise the present and make current ‘meat culture’ appear ‘strange’. A central aim of this research is to develop a new artistic methodology that I call ‘Visual Utopian Experimentation’ (VUE). This is distinguished from other visual futurity in key ways that will be described in this chapter. In doing so I draw on Levitas’ Utopian method which aims to help us understand and change the present from the perspective of a ‘good’ future. Levitas Utopian method is a Sociological method – I propose it can be developed as an artistic method. VUE is part of an overall political strategy/tool for change that hooks up with the potential of art as a political act for healing. The methodology for this research aims to facilitate healing of the human- farmed nonhuman relationship. It could equally be used as an approach for healing as a consequence of any human-human injustice.The method developed in this research is both an artistic expression, but also an example of “counterfactual imagination”: the creation of alternative futures based on hypothetical scenarios (Todorova, 2015). It will be argued in future chapters that this research and the wider method it embodies, offers a novel and significant contribution to developing new knowledge about the world; to understanding research and Fine Art as activist practices, while also suggesting new directions for research and methodology in this area. This methodological chapter provides a rationale and explanation for the key ideas guiding my practice – exploring and extending the concepts raised in this introduction in detail. The chapter starts with a word on time and temporarily as central to all futurities before discussing other approaches to visual futurity and speculation in the visual arts.

Time and Temporality in the age of the ‘infosphere’.

While contemporary visual art has paid attention to our perceptions of space (https://spacevoyageventures.com/space-in-contemporary-art/), there has arguably been less attention to perceptions of time; although temporality and temporal experience has become a greater focus more recently, perhaps particularly in performance art; and at least one book has been published in the last five years that discusses artworks that do focus on time (Kate Brettkelly-Chalmers, 2019). The futurist movement of the early 20th century should not be confused with visual futurity today. Futurism was an artistic movement that started in Italy and celebrated modernity in the early 1900s – speed, dynamism and new machinery. In contrast visual futurity today asks critical questions about capitalism, colonialism, consumerism, science and technology, resulting problems for life on earth, and changes to perceptions of time stemming from new technologies .

Stephen Kern remarked as far back as 1983 that new technologies had already drastically reshaped our experience of time:

Several new technologies transformed the experience of the present: the telephone, wireless, newspaper, cinema, and large city. They shaped a historically distinctive experience of simultaneity—the sense of being in, or having access to, two or more places at the same time.

Floridi considers time in contemporary society to be ‘Hyperhistorical’ (Floridi, 2010, 2014a). This term speaks to our sense that life seems to be getting faster, that time is speeding up, that so much appears to be happening at the same time or in a relentless stream of events, and that we can access so much information so easily and immediately. Floridi argues that life in the ‘infosphere’ absorbs much of energy and mental space, leading to a perceived need for speed above all else: “it’s getting harder for people to resist the temptation of speed first, direction next” (Lee, 2018). Mason and Bowden, (2023:3) draw on Savolainen, (2006) to suggest that we and our activities, specifically our information practices, are rooted in time and affected by temporal issues, as witness information overload, the attention economy, and attention distraction (Mason and Bowden, 2023 p; 3).

Sharma’s (2014) argument that our experience of time is constantly reconsidered and revised to match our environment and social relations, has been developed and extended by other writers, notably by Coleman and Lyon (2023), who distinguish three modes of recalibration: fissure, with an awareness of an unimaginable future, standby, with an alertness to a changed future, and reset, with a radical reimagining of the future. Fictioning, Radical Futurisms, and Utopian thinking in the visual arts involve the latter.

The term “heterochronia” (Foucault, date) tries to address the question of the politics of a time (chronopolitics) by looking into the relationships between language (representation, narratives), power, and temporality. This is both an epistemological question and a methodology for constructing history. Michel Foucault borrowed the term “heterochronie” from biological language in the lecture “Des spaces autres” (1967) to interrogate the modern Western construction of time and its relationship with hegemonic historical narratives. Heterochronia does not refer to time as an abstract dimension of physics, but rather to time as a social and political construction. Foucault thought of archives, libraries, and museums as “heterochronias”, political dispositifs that “accumulate time.” A museum works as a time machine that configures chronological and visual fiction. Mason and Bowden, (2023) ask: What are the times that museums are accumulating? And what other times resist conventional narratives and reject accumulation as a historical method?

Several visual futurities discussed below explicitly comment on time. For example, the exhibition ‘Just Futures’ (discussed in more detail below) considers how time itself is a site of struggle and a horizon of liberation. Java and Sims write, ‘Far from homogenous, inherently progressive, or equitable, dominant time expresses the 24/7 chronologies of capital, long synchronized to racialized, gendered violence and oppression. The seemingly endless meter of production encloses people in temporal holds, defuturing communities, and imposing time-traps of debt and deadlines’. https://sesnongalleries.ucsc.edu/exhibition/just-futures-black-quantum-futurism-arthur-jafa-and-martine-syms/

This thesis will bear in mind contemporary issues relating to time, and particularly question the notion that time is linear, objective and measurable, through use of clocks and by using minutes, hours, days, weeks, months and years. The experimental ‘Museum of Human Violence’ used as a device in this research, archives violences from the past, while existing in 2065, and is used as a technique to question this linear version of time. Building upon a critique of naturalized time already developed by Mikhail Bakhtin and Henri Lefebvre, Foucault’s notion of heterochronia opens up the possibility of understanding the museum as a collective abstract machine, not only to question the storyline of the past but also to invent “other” futures (Preciado, 2014). Perhaps the visitor to the artworks might ask ‘in what time do I exist?’ ‘what has brought me to this point?’. Interestingly, just as new-materialism, as discussed in chapter x, focuses on an ontology of becoming through entanglement of matter, so quantum theories of time have gone beyond Eysenck’s theories of relativity to theorise that time itself is produced through entanglement of matter. (Karen Barad is herself a quantum physicist and her theory of agential realism draws heavily on that discipline). At this stage in the research it is unclear how or whether the specific focus on time will become more central, but this is open to exploration.

Futurity in the visual arts

I broadly distinguish three ways that artists practice visual futurity, and suggest that there are further subsets, which can be attached to each. This distinction is somewhat simplistic since there are clear overlaps; it is nevertheless useful for me to understand my practice in relation to ways of playing with future time, as well as to identify which artists are inspirational for my practice, and why other practices of visual futurity are not useful for my research:

- Fictioning, (and Experiments in Imagining Otherwise)

- Radical Futurisms, (and Afrofuturisms/black futurity)

- Speculative art, (and bioart)

I have added the additional 4th category of ‘Fictions’ as a visual art practice using narrative in the conventional (but inspirational) sense of story telling. This may or may not play with the future – the fiction may be set in the present, past, future or in an indeterminate time and the goal is most usually focused on telling a story rather than enacting justice-to-come as a method for bringing it into being.

(1) and (2) above also overlap to a considerable degree, but in my view, have enough differences to warrant separate categories.

| Model | Key purposes and focus. | Explicit or implicit ideas about time?Utopian/dystopian | Key activities/ theme. Extent of ‘World building’ | Examples of artistic practice |

| ‘Fictioning’ (title of a book by Burrows and O’sullivan, 2021). Both artists. | Engender justice to come. | Explicitly recognises importance of chronopolitics. Hopeful but not explicitly building on utopian thinking. | Mark out trajectories different to those which our current systems seem to suggest. World building may be important. | Plastique Fantastique ( founders: Burrows and O’Sullivan) |

| ‘Experiments in Imagining Otherwise’ (title of a book by Lola Olufemi). Olufemi is a creative writer and curator. | ‘Thinking revolution in service of every living thing’. | ’A knowledge that knows there is no certainty, rather than some ‘utopian blueprint.’ | ‘Imagination is an exercise to extricate oneself from multiple oppressions enacted by patriarchy, capitalism, and colonialism. Experimental prose and poetry. World building not a central focus. | Lola Olufemi (I might have placed Olufemi below in the ‘afrofuturism’ section but I see perhaps more similarities with Fictioning, (I do not know whether she identify herself with afrofuturism or with Fictioning). |

| ‘Radical Futurisms’ (title of a book by T. E. Demos, 2023). Demos is a writer and curator of ‘Just Futures’ see below and ‘Beyond the World’s End (subsequently title of a book)’. | Critique current oppressive systems | Slightly less clear about the dystopia/utopia divide. Veering toward hopeful. | Critique capitalism and colonialism. racism and ecocide. World building central. | Thirza Cuthand’s film, ‘Reclamation.’ Just Future exhibition – see below. |

| Afrofuturisms/ Black futurity | Celebrate the strengths and achievements of people of African descent. | Utopian.Chron-opolitics often a central focus. | Offer a counter narrative of hope, strength and justice to come for oppressed peoples. Critique capitalism and colonialism. racism and ecocide. World building central. | Alisha Wormsley Black Quantum Futurism, (Moor Mother, Rasheedah Phillips), Arthur Jafa, Martine Syms. https://sesnongalleries.ucsc.edu/exhibition/just-futures-black-quantum-futurism-arthur-jafa-and-martine-syms/ Black Speculative Arts Movement (Reynaldo Anderson and John Jennings) . https://www.bsam-art.com/what-is-bsam |

| Speculative art | Imagines and describes outcomes of current (toxic) trajectories. | Tends not to be involved in discussions of time itself as a site of struggle. Dystopian/ questioning/ raising awareness | Offer a warning/give pause for thought about where current systems are leading.World building important but limited to issues explored rather than across all systems. | There are many examples of artists working in this method. Here I mention only two whose artwork includes reference to human-nonhuman entanglement -Alexis Rockman -Patricia Piccinini |

| Bio-art (term attributed to Eduardo Kac). | Synthetic bioartists use genetic engineering to make new life as a way to bring to attention issues surrounding genetic engineering. | As above in relation to time. Bioart may be hopeful (for example Catts and Zurr (victimless leather). | May offer a warning but may also offer ‘solutions’. Doesn’t explicitly focus on human relationships. Because the focus is Science it tends not to touch on social issues including capitalism, colonialism, inequality. World building only in relation to biological worlds. | Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr (founders of SymbioticA and the Tissue culture and art project). See: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/110251?artist_id=33104&page=1&sov_referrer=artist Eduardo Kac Mark Stelarc Amy Karle Suzanne Anker (founder of the SVA bio art lab at New York City Uni art department) |

| Fiction: imaginary characters, places, scenarios. | Artists have used narrative and fiction in their work for a long time without using it ‘to fiction’ alternative futures as a way of critiquing the present. The group of artists considered here perhaps use fiction in the same way as novelists fictonalise individuals and situations. | These artists play with time but not as a site of liberation or of struggle. Visual futurity, as its name suggests, looks to the future. Fiction generally might be set in the past, present or future. | Fiction is used as in literary fiction, mainly to tell stories; as with a novelist, their themes may touch on trauma, memory, class and gender. World building fundamental but not necessarily future world building. | Barbara Cleveland. Donelle Woolford. Reena Spaulings. https://openaccess.uoc.edu/bitstream/10609/68545/4/3122-13287-1-PB.pdf https://dismagazine.com/disillusioned/65965/the-trouble-with-donelle-woolford/ Iris Haussler, Zoe Beloff , Sunny Allison Smith and Ilya and Emilia Kabakov |

All visual futurity asks the audience to look forward to an imagined future but there are differences between each, including the aims/purpose and whether these relate to social justice (stated or implicit) and the specific goal of engendering ‘justice-to-come’; whether the envisioned future is dystopian or utopian or neither; the emphasis on temporal heterogeneity and Chronopolitics; and whether the goal is to reimagine a different future for all living beings, or the human. only, or perhaps only some humans.

Fictioning

Burrows and O’Sullivan (2021) define Fictioning as ‘practices which fiction parallel or alternate perspectives’ (ibid. p. 76). They write that they use Fictioning:

… as a verb to signal the marking out of trajectories different to those engendered by the current organisation of life, as well as fiction as intervention on, in, and augmentation of, existing reality.

They argue, fiction can take on a ‘critical power’ when it is set against a given reality. Fiction, in this sense, is intervention on, in, and augmentation of, existing reality’. It engenders justice-to-come. Fictioning is inherently critical of dominant discourse; it is anticapitalist and anticolonialist. Burrows and O’Sullivan agree with Statkiewicz (2009) that fictioning involves a collapse of hierarchies between art and philosophy – and point out that philosophy has long been concerned with modes of narration and play that produce truth or unconcealment. The philosopher Heidegger was particularly interested in the idea of unconcealment in art. Romanow (2013) writes about Heidegger’s thoughts on defamiliarisation and truth::

Truth is not essentially a correspondence of proposition and state of affairs; it is essentially a making present. In art, whose essence is poetry, “language brings what is as something that is into the Open for the first time” (ibid. 694). The essence of truth is “unconcealment” and this is effected principally by art. (p.5)

Burrows and O’Sullivan write that fictioning is most powerful in art when there is a play of fiction AS life and reality: in other words, a blurring between ‘fact’ and fiction.

O’Sullivan’s (2016) argues that an artist of any kind cannot escape from the dominant ideologies – they are always ‘in the world’. This reminds me of Hans Haacke (1974) whom I have been reading about in relation to Institutional critique:

Artists as much as their supporters and their enemies, no matter of what ideological coloration , are unwitting partners …They participate jointly in the maintenance and/or development of the ideological makeup of their society. They work within the frame, set the frame and are being framed.

I know from previous experience of working on gender issues, that pointing out problematic belief structures and behaviours that result in injustices merely compounds the injustice if it is being pointed out to someone who does not already experience it. Describing /showing/pointing out is, not a critique. I learned instead that work to critique oppression must avoid violent imagery and build on participation and engagement as a starting point.

I struggled with this fact of ‘being in the world’ before I adopted fictioning – it would be suggested to me for example that I might recreate explicit violence to the nonhuman. O’Sullivan’s (2016) writes that, as a counter to ‘being in the world’, Art should operate on the edges of the viewer’s understanding. O’Sullivan recognises that this might lead to responses of frustration, boredom, annoyance, or irritation. The danger I see is that these responses may push people away. I think, instead, that the artist must find a way to engage empathy and interest in the idea of future possibilities for a different world, and that the fictioned world should make sense as a possible outcome of our current trajectories .

In fact, O’Sullivan 2016 writes that an important aspect of fictioning in contemporary art is that the audience must participate in the fiction (perhaps less likely if they are frustrated, or bored).

Add something on myth-science and mythopoesis (world building)

Experiments in Imagining otherwise

Lola Olufemi’s (2021) writing is based on a commitment to Black feminist and anti-colonial thought. She makes prose and poetry experiments, as she contemplates a future in which our modes of relating are transformed. She also curates visual art exhibitions, for example, Acts of Resistance: Photography, Feminisms and the Art of Protest at South London Gallery (2023), together with the V and A, London I visited and very much enjoyed this show). Like others working with ‘futurity’ she sees the imagination as central to revolutionary movements for change. She, along with writers mentioned so far, imagine that the ubiquitous capitalist /colonialist/anthropocentric path we tread is mutable, and that the arts have a role in this transformation. Crucially, ‘imagining otherwise’ disrupts the social order. As Earle, (2019:3) wrote:

… it is possible to imagine ourselves differently. It is incumbent upon us as readers, citizens, and authors to do so more often, in more ways, and including more kinds of people. Only through different imaginings will the world’s oppressive structures shift.

It is for these reasons that I see the work of Olufemi as being aligned with the ‘fictioning’ of Burrows and O’Sullivan.

This focus on the intersectionality of violence and oppression also stresses the importance of not only imagining a better world, but looking at our own values and behaviours to ensure, as best we can, that we do not collude in multiple oppressions:

For Olufemi, imagination is not solely, if at all, about a cerebrally crafted utopia. It is an exercise to extricate oneself from multiple oppressions enacted by patriarchy, capitalism, and colonialism. Through her lists of ‘some places they would like us to forget’, she shakes up the reader to remind them how feminism is about ‘revolution in service of every living thing’. Herein lies the book’s greatest appeal: Olufemi is asking that we reimagine social relations and recognise the dire need to reorganise them.’ ( Ashtekar, 2022)

Of all the artists working with visual futurity, I have so far found that only Olufemi specifically mention ‘every living thing’, which I take to include the farmed nonhuman. This quote above from Ashtekar’s (2022) review of the book highlights that while Olufemi’s imagining starts from a Black Feminist perspective, she invites us to imagine a world in which our relationship to all life is reimagined: ‘I feel embarrassed when I say feminism and people do not think revolution in service of every living thing‘ (Olufemi 2021, 13). ‘Like Burrows and O’Sullivan (2021), Olufemi stresses the importance of the imagination as a tool for conjuring. The act of imagining is in itself a powerful way of bringing into being. We therefore need to be careful what we imagine.

In common parlance, the imagination is understood as the process of conjuring that which does not exist—presently or subjectively. To imagine, then, is to conjure an idea, a feeling, a thought, a sensory or affective response that was not present before the act of conjuring it began (Olufemi 2021, 27).

In terms of such conjuring, imagination lets us glimpse what is not there and gain a sense of its possible presence in the first place. However, for Olufemi, radical political imagination has to be distinguished from her understanding of utopianism. Olufemi seems to view Utopia as a plan, when she states that while the traditional utopist knows precisely how the future society should be arranged, imagining otherwise in Olufemi’s sense means first to expose oneself to the unknown and to embrace this exposure: “The otherwise requires a commitment to not knowing.” (Olufemi 2021, 17) The alterity of political imagination involves a “knowledge that knows there is no certitude” (Olufemi 2021, 124). Instead of counting on moral progress or a historical tendency that inevitably leads to the better, radical politics on Olufemi’s terms makes a different use of imagination, an intensified use that familiarizes with how political action always remains venturous.

Olufemi’s writing has been important for my own work from the beginning. Although I sympathise with her statement that ‘knowledge that knows there is no certitude’ and the commitment to ‘not knowing’ or to not counting on or imagining a utopian future, I believe utopian imagination is important (see below). In fact I was surprised to read her cautioning against utopian imagination, because I felt that the ‘Acts of Resistance’ at South London Gallery, curated by Olufemi, left no loophole for imagining anything other than a feminist future in which women resist oppression. For me this relates to the question of taking a position in the Arts: we are sometimes told that ‘good’ visual arts are open to interpretation. In my view some visual arts can be open to interpretation, for example, abstract paintings, and those works that are not obviously ‘political’/focused on injustice or exploitation. However, where issues of Justice are forwarded, there can be no doubt that the artist is on the side of Justice. i.e. non exploitation/non violence/non cruelty/non oppressive. This does not mean works are necessarily didactic, or that if they are didactic this is necessarily a bad thing. I will write more about this at a later time.

As I wrote earlier, chronopolitics is important for work on futurities, and can be understood broadly as the relationship between human perspectives and time. Importantly, Olufemi is also interested in hegemonic temporality. Their book can be read as attempts to disorient the linearity of time, bending it to form nonlinear shapes. In this view, linear, synchronous temporality is the temporality of modern dispositives of domination, both in its progressive and conservative variants. In relation to time, Ashtekar (2022) writes of Olufemi:

Her generative vision makes us rethink temporality – time becomes memory after one has experienced it. Olufemi confronts our preoccupation with time to go beyond the experiential and into the experimental’ (Ashtekar, 2022)

Sergei (2022) points out that Olufemi uses the symbol of the circle and writes that what is attractive about the circle, for Olufemi, is that it invites to think of past, present, and future not as neatly divided but as interwoven and superimposed onto one another in complex ways. This is reflected in the book’s tripartite structure, where the three chapters are captioned as “Past (Present / Future),” “Present (Future / Past),” and “Future (Past / Present).

Radical Futurisms

This is the title of a book written by T.E. Demos (2023). As with Fictioning, Radical Futurisms view contemporary arts as having a role in changing the world through imagining a future that is fundamentally different from the present: structurally, economically, and politically. Demos writes that RF’s ‘remake time’:

‘They derail temporal trajectories from present tracks, casting the what’s-to-come into the undetermined not-yet. As modalities of chronopolitics…they de-essentialise and de-normalise time, operationalizing its becomingness anew in the formation of other worlds’ (p. 19).

RF is anti-capitalist and anti-colonialist. RF, like Fictioning, sees artistic interventions as transformative and generative. Both can perhaps be argued to be more interested in a future-to-come, or justice-to-come, than with defamiliarising, or approaching the familiar from a fresh perspective (the goal of this research). Fictioning appears more focused on the nonhuman than does RF, with many examples and references to other species (Plastique Fantastique for example), but the oppression of farmed animals is largely overlooked in both Fictioning and RF. In other respects RF has a different emphasis to Fictioning. RF focuses largely on building solidarity for a democratic post capitalist future, while Fictioning focuses on the importance of fictioning itself as a method to bring into being ‘different becomings’, that might include part human, nonhuman and human. This emphasis on trans species or transhuman/cyborg becomings is not a concern in Demos’ book. RF is more strictly focused on bringing about greater equality for the human. Demos has curated visual art shows, including ‘Beyond The End of the World’ (which became a book) and ‘Just Futures’ (see below in the section on afrofuturism). He starts ‘Radical Futurisms’ with the example of Thirza Cuthand’s film ‘Reclamation’ as an inspired Radical Futurist short film. He also draws on several other examples from afrofuturism. TJ Cuthand’s film, manages to be both humerous and highly critical: In this short film, the whole of the global White population have left to colonise Mars, after colonising Canada, where the film is set, and trashing the Earth. They have left the indigenous populations behind to clean up their mess. The film consists of interview with three of those left behind who reflect on life before the White people left, compared to life as it is ‘now’. They generally prefer the ‘now’. (https://vimeo.com/279943832).

Reclamation. 2021. Thirza Cuthand

Reclamation” is a documentary-style imagining of a post-dystopic, indeterminate, future in Canada after massive climate change, wars, pollution, and the after-effects of the large scale colonial project. The Director, TJ Cuthand is themselves indigenous Canadian.

As I wrote earlier, the colonisers have now moved on. The indigenous people are very glad of this, although they have been left behind to clean up and heal the damaged world. This film is influential for me for a number of reasons: its concept is simple and told through humour – making it accessible to any audience. The themes are clear – the greed of colonisation; the exploitation that colonisation brings to the environment and to the indigenous people living in that environment. These themes are inseparable in the low tech, low budget approach to making the film; through interview, interspersed with ‘found’ images relating to what the interviewees say.

Image: White humans leaving earth to colonise Mars

Afrofuturist visual arts

As I have already pointed out, Demos largely draws on the work of Afrofuturist artists to illustrate Radical futurism and they are closely related. This paper now turns to the work of other Afrofuturist artists who use visual futurity to raise awareness of race and queer justice, for example the work of the The Otolith Group; Black Quantum Futurism (Moor Mother, Rasheedah Phillips); Arthur Jaffe; Martine Syms. In Black Quantum Futurism: Theory & Practice (Volume 1) Moor Mother and Phillips propose “a new approach to living and experiencing reality by way of the manipulation of space-time in order to see into possible futures, and/or collapse space-time into a desired future in order to bring about that future’s reality.” The book argues that quantum mechanical interpretations of time, spacetime, causality and interactions are more in agreement with Afrocentric understandings of these same phenomena than with Western ones, and that methodologies which merge these ideas will be able to counter Eurocentric, colonialist structures and conceptions of reality.

AF’s work centers the subjective and cultural nature of time itself, and its material impact as a tool for both the oppression and the survival and liberation of Black people and communities. They claim that Manifest Destiny and westward expansion were as much about time as space; a laying claim not just to the land but to the future and who determines it.

All futurities discussed so far involve making interventions that are transformative and generative: afrofuturism has the same goal.

- The Just Futures show, curated by T.E. Demos, was at Sesnon Gallery, Santa Cruz in Feb-March 2022, featuring Black Quantum Futurist artists; Arthur Jaffe and Martine Syms. The exhibition formed part of ‘Beyond the End of the World’ project, which comprised a two year-long research and exhibition project and public lecture series, directed by T. J. Demos of the Center for Creative Ecologies, bringing writers and practitioners together to discuss what lies beyond dystopian catastrophism, and asking how radical futures of social justice and ecological flourishing could be cultivated.

The Black Quantum Futurism exhibition, 2020, featuring Moore Mother, Rasheeda Philips, Arthur Jaffe and Martin Sims, held in Toronto, also explicitly focused on time.

Black Quantum Futurism, Nov 16-Dec 13, 2020. “Black Womxn Temporal Portal,” Radical Hope series – Burning Glass, Reading Stone group exhibition, Blackwood Gallery at the University of Toronto Mississauga,

2. Alisha Wormsley

Perhaps Wormsley’s most well known works is her project ‘Children of Nan’. This is an arcive of objects, photographs, videos, films, sounds, myths, rituals, stories and performances compiled over two decades (https://www.alishabwormsley.com/nan). On her web site Wormsley writes:

This project understands the ways black womxn have taught one another to care for humans and the earth – respecting and understanding the earth and astronomy in order to grow plants, craft medicines, prepare food, support healing, and connect to their ancestors and to the spiritual realm. This matriarch holds the most advanced technology…..

Wormsley started the project using material collected for other projects. Like Cuthand’s film, it is rooted in an apocalyptical future where only a group of black femmes called Abassi and a group of white men lead by the ‘scientist’ exist. Working laterally with history these groups have been at war since the beginning of humanity. Aditi 34, the protagonist, was made in a lab by the “scientist” using kidnapped Abassi, Nan. Aditi 34 has 3 sisters, Aditi 35, 36 and 37. One by one their sisters disappear. 34 leaves the lab, goes above ground, to find them. They are led by a mysterious guide who is a portal through time she goes a discovery to find NAN. Wormsley writes that she created the Children of Nan Archive as a survival guide inspired by Black womens’ legacy of survival and prophesy for their future.

I am inspired here by Wormley’s commitment to the project and by her multi layered/multi media approach to world building. Like Cuthand, she too uses an intersectional approach that is critical of the exploitation of both people and land.

More recent work from Wormsley draws on the Children of Nan to build a new archive of Black women.

(Remnants of an Advanced Technology, 2022, Hunterdon Art Museum)

I especially like both the aesthetics and the concept of this installation. The title, too, invites the audience to consider what these remnants might mean in relation to Technology, the future and the people to whom they might have belonged.

Speculative art

Alex Rockman is also a North American artist. They are primarily a painter who makes works that depict future landscapes that have been impacted by climate change and evolution influenced by genetic engineering. As such of the three artists discussed here, their theme is most closely related to my interest because they explore both the future and genetic engineering, including the implications of genetic engineering on the farmed nonhuman. But their method is less related.

Alexis Rockman. Spheres of Influence. 2016. Oil and alkyd on wood panel. 72 x 144 in.

Alexis Rockman. Chimera. (detail)

Rockman, unlike Cuthand or Wormsley, imagines a nightmare dystopian future resulting from human excess and unsustainability. For me, this fact distinguishes their work from either Cuthand or Wormsley. While Rockman is clearly anticapitalism and anticonsummerist, they do not, like Olufemi, or Wormsley or Cuthand, ‘Experiment in imagining otherwise’: rather they represent the dystopian picture that is presented by the environmental movement. The work, although aesthetically beautiful, does not give hope. In my view they do not meet Earle’s (2019) insistence that ‘Only through different imaginings will the world’s oppressive structures shift.’ For this reason for me they do not fit the definition of Fictoning by Burrows and O’Sullivan as ‘a verb to signal the marking out of trajectories different to those engendered by the current organisation of life, as well as fiction as intervention on, in, and augmentation of, existing reality’ or engendering justice-to-come. This is not to dismiss their work – all work focused on our relationship to the more than human world is welcome to me. Rather it is to help clarify how my work may differ.

Bioart

The term ‘bioart’ was coined by the Brazilian American artist, Eduardo Kac (born in rio de Janeiro in 1962) who is known for his works creating genetically altered organisms. He also called these creations ‘gransgenic art’. ‘Genesis’, 1993, was Kac’s first genetically engineered creation. He translated a passage from the Christian Bible into Morse Code and then into the four-letter code that represented the base pairs of DNA. He commissioned the creation of synthetic DNA using that sequence, and it was injected into bacteria, images of which were projected onto a gallery wall. In 2000 he showed photographs of GFP Bunny: a rabbit engineered to express the green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequoria victoria. The rabbit in photographs is green, but in reality only the living tissue glowed green under blue light of a certain wavelength – the rabbit itself did not glow green. Controversially, the French Agronomic Institution claimed that they created and ‘owned’ the rabbit and had created multiple rabbits that expressed the protein: GFP was a common tool in cellular research. In 2001 Kac exhibited a project that consisted of a collection of transgenic animals contained in an acrylic dome. His later work has developed to focus on bringing art into space.

More interesting to me, because more obviously exploring the ethical and justice issue that arise when we ask, What is Life? are the artists Oron Catts, current director and cofounder of SymbioticA, an artistic research centre based at the University of Western Australia’s School of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology, and Ionat Zurr, an assistant professor and academic coordinator at the centre.

Their “Victimless Leather” experiment was shown at MoMA New York’s Design and the Elastic Mind exhibition, which was seen by more than half a million people in 2008. “We are artists/designers working with semi-living beings,” (https://www.wired.com/story/catts-and-zurr-synthetic-biology-rca/): “We grow/construct carbon-based life forms made of living fragments of complex bodies, which are sustained alive through artificial support mechanisms, and are always potentially dying. “It can be argued we are following an intrinsically human practice of exploring and exploiting life through manipulation.”

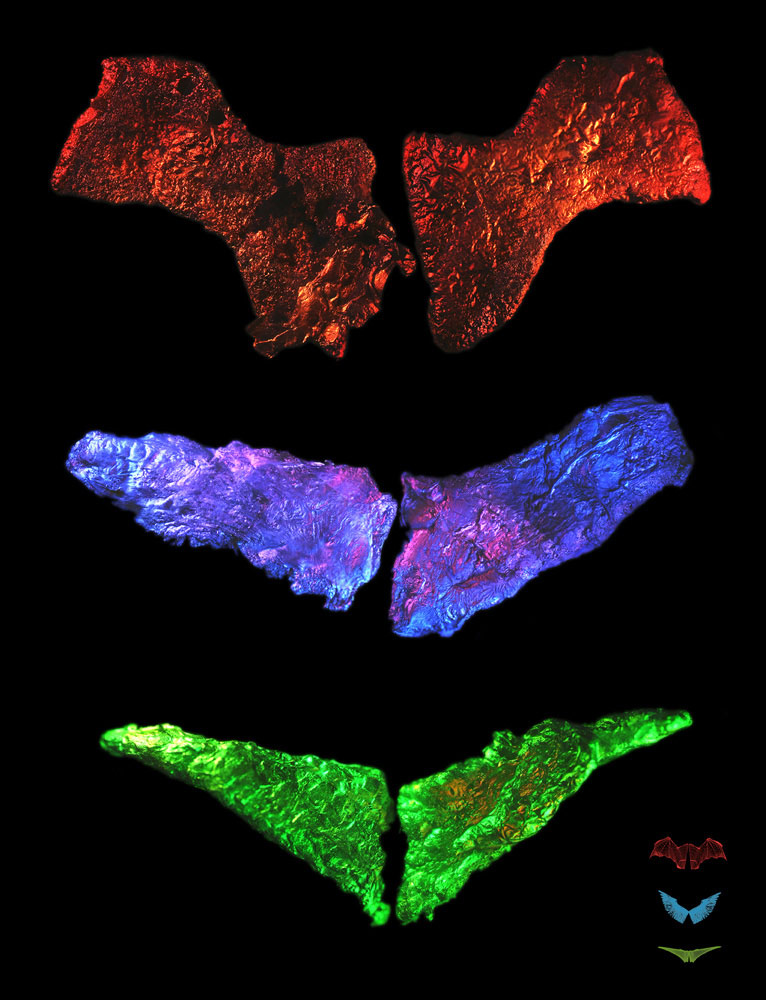

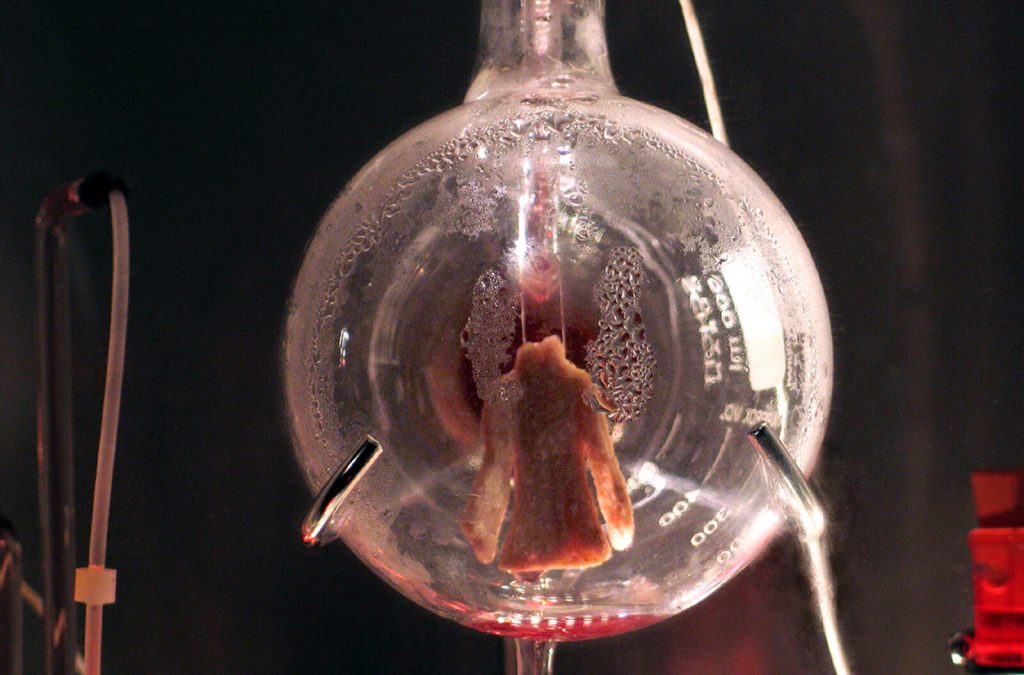

Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr. Pigs Wing Project.

Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr. 2008 Growing victimless leather.

Catts and Zurr stress: “Our intentions are non-utilitarian, non-instrumental and open to debate. Rather than celebrating the technological approach to ‘life,’ we look at how life asserts itself as a context based materiality, defying human and technological controls.” “We celebrate failure and embrace futility, we rejoice life.” These artists are asking the question of what, in the near future, is life itself? The work of these artists is clearly close to my own interest in bioengineering, biocapitalism and biopolitics. In my opinion it is important to draw attention to where bioengineering might lead us and to pose the questions of ‘What is Life?’ And ‘What ethical issues arise when Humans(and artists) take on the role of creating life? It should be emphasised too that Catts and Zurr draw attention to human exceptionalism when they state that they are following the human practice of exploiting life.

I have placed bioart in the same category as speculative art because the artists themselves say they are exploring the question of what is likely to happen in the future – given the path bioengineering is taking.

While synthetic biology focuses on the particularities of each micro-manipulation within a specific timeframe, art practices can speculate on the wider reverberations of modified life, making visible the vulnerable encounters and uneven exchanges across variable living forms and scales, from molecule to human, synthetic to organic (Johung, 2016: 175)

Bioartists are projecting the outcomes of current technologies into the future to ask questions and raise awareness of where these may lead. Bioart and other speculative arts do invite us to look at the present with a critical eye. However, the element of ‘imagining other’ is not so clearly present in this work. Bioart is also different from the model proposed in this research in that, like Radical Futurisms, Bioart requires the audience to firmly imagine themselves in the future. Chronopolitics is perhaps not a concern of bio artists. Bioartists do not obviously play with time in the sense of questioning time as linear. Nor is bioart or speculative art necessarily critical – it does not specifically focus on human relationships with the more than human and human injustices.

Fiction

I have written at some length about the artists Iris Haeussler, Zoe Beloff , Sunny Allison Smith and Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: see https://susanaskew.uk/context-artists-who-incorporate-installation-with-fiction-or-fictioning/↗

Here I include a few notes only on ‘The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach’ (2006) and ‘The Joseph Wagebnbach Foundation’ as an indication of the narrative approach taken by Haeussler that is both focused on a fictional narrative of an individual artist, as well as a ficitonal institution that collects actual artefacts purportedly made by this person. I have chosen to write a little more about this work because it is closest in some ways, to my own work: I too have a number of fictional characters in my work: Nasus Y Ram, a fictional artist; and Weksa Nosmada, the fictional director of the fictional Museum of Human Violence. Like Haeussler’s ‘Foundation’, the Museum of Human Violence archives the real works of these fictional beings.

The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach (2006) was Iris Haeussler’s first major work in North America and her largest and most complex installation at that time. “The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach” recounts the life of an aged, reclusive artist, through the mediation of an on-site archivist (often Haeussler herself). A fictitious institution called the “Municipal Archives” was established, ostensibly to assess the old man’s legacy after he became incapacitated.The Municipal Archives organize guided tours through the house where visitors could not only see the chaotic accumulation of artworks but also get a glimpse into his daily life. Initially, the project was not publicized as an artwork but presented as an assessment by the fictitious “Municipal Archives”. Haeussler intended to facilitate an unfiltered and unhindered experience of discovery. The subsequent disclosure sparked controversy on the ethics of engaging uninformed visitors in an often emotional encounter with a fictional narrative that is initially presented as fact. The Joseph Wagenbach Foundation was a longer-term project, resuming from the 2006 installation and expanding Wagenbach’s legacy into a fictitious foundation. Launched officially at the Villa Toronto in January 2015, it offered small edition bronzes of a number of his sculptures and a drawing edition to the public. The foundation worked on digitizing his drawing and sculpture archive, and planned on the dissemination of his work and life,

Haeussler writes:

About the Foundation

‘The Wagenbach Foundation was founded three years after the discovery of Joseph Wagenbach’s life and oeuvre. The reclusive immigrant from Germany had created a pandemonium of sculptures in his small house on Robinson Street, Toronto, where he had resided since 1962. After a severe stroke in 2006, Wagenbach was not considered well enough to live on his own and forced to reside in several retirement houses, before he was taken to a basement apartment at Crawford Street, Toronto. However in summer of 2007 he disappeared from there, traceless to this date.’

Mandate of the Foundation

The Joseph Wagenbach Foundation manages Wagenbach’s artistic legacy. This encompasses the archiving of his works and research into his biography, the creation of a digital inventory, the organization and curation of national and international shows of his work and the dissemination of information about his Art work. The institute also issues limited edition prints of select drawings and bronze casts of his original sculptures. https://haeussler.ca/projects/joseph-wagenbach-foundation.html

Some of her work seems connected to exploring memory, but other work is more closely about exploring trauma, as well as class and gender issues. I don’t see evidence that she is using Fiction in the sense of ‘to fiction’: as used by Burrows and O’Sullivan and Lola Olufemi: to generate or bring about. Another difference in approaches is that Haaeussler (whose work I admire), works on major fictional scenarios in sequence – using different scenarios and characters in each with a different focus – while my work is made for the museum of human violence with the goal of defamiliarising values and behaviours to the nonhuman.

Haeussler’s most recent fiction is titled, ‘Seventeen grams of longing’ in which she uses the fictional story of two brother’s fascination with bird migration motivated by thier own traumatic experience of separation in world war two: 17 grams is the average weight of a migrating songbird.

Iris Haeussler. Seventeen grams of longing 12.

Iris Haeussler. Seventeen grams of longing 16.

While differences exist between using Fiction and Fictioning in Art here is a lot to learn from her work, which manages to be conceptually interesting and aesthetically beautiful at once: it can be enjoyed on many different levels.

Summary

In summary, Fictioning is concerned with generating justice-to-come: imagination is viewed as an important technique for doing so. Fictioning is perhaps influenced by postmodernist thinking and writing. Post humanist writers such as Braidotti and Haraway also focus on the importance of fictioning. Braidotti (2022: pp 224-229) writes about Afrofuturist fiction, for example the work of Octavia Butler and N.K. Jemisin:

The authority and trans-formative energy that are missing from a traumatic past and the harsh conditions of the present can be borrowed from the future, defined as a site of empowerment to come (p. 226).

Haraway, goes beyond suggesting fictioning, to using it as a ‘method’ herself: ‘Staying with the Trouble’ (2016) ends with the fictional story of five generations of Camilles’ who inhabit the devastated earth during the next 400 years. Humans are given monarch butterfly genetic patterning to enable them to relate to butterflies, and work with them to make their continued existence a possibility.

Crucially, imagining differently disrupts the social order.

Visual Radical futurisms are also concerned with justice-to-come, with disrupting the social order, and with time, but perhaps their focus is more obviously on justice for the human/environmental issues, and less on the nonhuman/transhuman /cyborg. Demos (2023) is particularly interested in the role of the creative arts in supporting solidarity for an alternative democratic anticapitalist and anti colonial future.

Rather than imagining a different trajectory for the future as a method of justice-to-come, Speculative art, including bioart is concerned with pointing out/raising awareness/asking questions about the current trajectory of modern life, including the new biology/synthetic biology. ‘Remaking time’ is not a central preoccupation.

All futurities discussed are unsurprisingly, focused on the future, whether bringing about a better future or raising concerns about what kind of future we are headed for. (Fiction itself may not be focused on the future). The extent to which the different futurities ‘world build’ varies, as does the extent to which the imagined world is cohesive and involves all aspects of society. The methodology for my own research is focused on world building for a better future that is underpinned by values of peace which infiltrate all aspects of living. However artistic making is concerned with world building only to the extent that it helps the artist/viewer understand and perceive the present differently, and so that we may live in the present as if that future were a reality.

Kester (2010: 23) describes the most common experience of contemporary visual art as ‘individual, visual and sensory’. He writes about moving toward a ‘dialogic practice’ which necessitates discursive exchange and negotiation. My experience of working with visual futurity suggests that it provides a useful framework for moving toward such dialogic practice: essential for any artwork that purports to be concerned with social justice/critical commentary.

Visual Utopian Experimentation: a new methodology for visual research

As I wrote at the start, a central aim for this research is to develop a new visual methodology as a contribution to knowledge about practice-based visual art research as a political strategy/tool for change. I call this Visual Utopian Experimentation (VUE). I do not claim that this is an entirely novel and unique research methodology: I borrow from fictioning (Burrows and O’Sullivan, 2019) , experiments in imagining otherwise (Olufemi), 2021 and radical futurisms (Demos, 2023). However, VUE has some distinctive characteristics that mark it out as different from other futurity in important ways. In this section of the paper I outline some key Sociological and Philosophical ideas that inform the development of this methodology.

In my original research proposal I described a Utopian approach to my visual art practice. I did so because I strong believed that in a time when radical change is so necessary, it is important to be hopeful and hold out the expectation of change for the better, rather than dangling terrifying warnings that perhaps are more likely to cause despair and helplessness. I wrote that my methodology would be Fictioning. However, further writing here on the various visual futurity methods made me realise that my methodological approach was different in important ways. I searched for writing that might turn Foucault’s work on archaeology on its head – instead of digging up the past in order to understand the present, the method might involve building a hopeful future in order to understand the present. I also used ‘Utopias’ in my search terms. I discovered the work of Ruth Levitas, (2013, 2017), Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of Bristol. I am particularly indebted to her book, ‘Utopia as Method’, and paper, ‘Where there is no vision, the people perish: a utopian ethic for a transformed future.’ She writes, ‘Utopia encourages us to think differently, systematically, and concretely about possible futures,’ (2017: 7).

A starting point for Levitas (2017) is that thinking about ethical responsibilities in the present and for the future is ‘helped by looking through the lens of Utopia’ (page 1). She points out that much discussion of ethics separates thought and feeling. She writes that this is deeply problematic, ignoring our embodied human nature and complex social relationships. Levitas argues for a Utopian approach that enables our thinking about ethical responsibilities in the present and for the future .

The Utopian approach allows us not only to imagine what an alternative society could look like, but enables us to imagine what it might feel like to inhabit it, thus giving a potential greater depth to our judgements about the good (p3).

This focus on the importance of both thought and feeling chimed with my growing awareness that the artist’s empathy/compassion for their viewer must be central if they aim to engage viewer empathy and compassion for the plight of the nonhuman. I tend to focus too much on the ‘educational’ aspects – pointing out and explaining. A shift in my thinking began with thinking about work for an exhibition at the handbag factory (a South London art gallery) in the first year of my research, when I realised I was once again ‘telling’ and focused on viewer learning, rather than empathising with my viewer as a first step to my viewer empathising with the victims of the leather industry (I was making site specific work). The main text of this ‘virtual workshop’, made as part of the installation, shifted from education to an empathy:

Levitas agrees that Utopia has come to be regarded as unrealistic idealism, at best, and violence, oppression and totalitarianism at worst.

The politics of this kind of anti-utopianism are essentially conservative: they run counter to radical change, and even where they purport to allow gradual change, this is essentially tied to the present (Levitas: 2017, p 6)

In actuality, Levitas writes, the defining characteristic of utopian thought is the desire and hope that things might be otherwise, and might be better. She writes that the original purpose of Utopia, as used by Thomas More was to describe an alternative society. ‘This more holistic version of the utopian mode treats social arrangements, means of livelihood, ways of life, and their accompanying ethics as an indivisible system’ (page 6).

The other way of thinking about Uopia, that Levitas suggests, concerns ‘prefigurative practice,’ that is, an attempt to live the relationships and practices that might characterise an imagined better future. This is the ethic underpinning ‘Visual Utopian Experimentation’ (VUE) in the Museum of Human Violence: not only do the virtual Museum staff live this out, but as a researcher I attempt to live my life according to the values of the Museum: so this is a methodology that involves personal ethical responsibility as well as ethical responsibility for the research outputs.

Writing about Utopia and time, Levitas exactly captures what I am setting out to do in the MHV in a way that I have not found expressed in other writing on visual futurities:

There is a sense, then, in which all utopian speculation is about the present rather than the future. It addresses those issues that are of concern in the present, by projecting a different future in which they are resolved. Nevertheless, the degree of distance offered by Utopia is important. It enables a kind of double vision in which we can look not only from present to future, but from (potential) future to the present. (page 7)

in a similar vein:

Utopia helps us here too, by providing that double vision between present and future. We can imagine a future society with a different ethic, and look at our own practices from that standpoint. Utopia offers a base outside from which to critically observe the present. This imagined future is the projection forward of traces, such as an ethic of care, which already exist, albeit embryonically. At the same time, it is a contradiction of the growth-based, profit-based, property-based, ecologically damaging present. (12)

Miguel Abensour (1999) argued that this process of imagination also enables people to learn to want differently, by thinking and feeling themselves into an alternative world. He called this ‘the education of desire’. Levitas stresses that Utopian thinking involves thinking about all aspects of society – it highlights that all belief systems are inter-related as are all organisational systems – schools, prisons, families, law and so on. Utopian thinking therefore means we must think about how our imagined society fits in the local and global ecology. Also we must think in concrete terms, rather than abstract terms such as fairness or equality. This utopian-sociological approach makes us think about how society works in everyday life – how our utopian society designs social institutions.

Levitas writes that anti-Utopian arguments represent Utopia as an unrealisable plan, and that this is mistaken. Utopian arguments are not a plan, they are a hypothesis – the imaginary reconstitution of society – is not a blueprint but a METHOD. The first step is architectural – imagining an alternative society. The second step is archaeological – subjecting the alternative to rigorous scrutiny and critique. The third step is ontological – involving discussion of what it means to be human , what is good for us and what makes us happy. From the perspective of the Museum of Human Violence, this is perhaps the most difficult step (perhaps it always is). But also, from the MHV perspective, these questions from Levitas have to be broadened to include, What does it mean to be human in an interconnected ecosystem? What is good for the ecosystem and for other beings we share this planet with? How can our beliefs about our own individual happiness shift to the pursuit of wellbeing for all?

This ethic of personal responsibility is present too in her suggestion that

‘to live for the future is to live in the present as a being not wholly determined by the present settings of organized life and thought and therefore more capable of openness to the other person, to the surprising experience, and to … time and change’. (12)

Levitas points out that the Utopian method is always subject to critique and always provisional. Importantly the utopian method is a process rather than a goal. ‘The imagined better future is not a plan to be implemented, but a beacon of hope and possibility, calling us to account and standing in judgement over the present’. (p13)

The Museum of Human Violence is such a beacon of hope.

Method

The central methods of research in VUE are ‘Fictioning’ (Burrows and O’Sullivan, 2019) along with Installation. The method of fictioning is most closely aligned to the goals of this research: to derail the exploitative and unjust use of the farmed nonhuman, to imagine a just and peaceful future where such behaviour is unthinkable; and to make the fact that it happens horrific. I imagine a Museum of Human Violence, opened in 2064 after the Giant Rupture – a major historical upheaval resulting from a bioengineering mistake, that directly lead to two billion human deaths and a rethink of the values that humans had lived by for several thousand years (particularly values related to accumulation and ownership). The guiding principles for making artworks are:

- hope for a world in which violence no longer exists (between the human and farmed nonhuman as well as between humans)

- compassion and empathy for human and nonhuman, both virtually and in reality for visitors to the artworks

- world-building is not the central goal for practice, but a point from which we perceive the present differently.

- the contemporary world of mid 2020’s is defamiliarised/made strange

- time is nonlinear, and past, present and future are conflated to some extent

- human values and economic organisation are fundamentally changed

- ‘unconcealment’: of the tools, practices, language that are used normatively to hide violence in the present

- researcher ethical responsibility in relatonships, behaviour, thoughts and practices

The role of the Museum is to hold memories of previous human violence, as well as to ask questions about how humans normalised violence and disocciated from violence to the nonhuman. Importantly for my work, I imagine a changed world from which to look back at the present/past to ‘defamiliarise’ current beliefs and values, and ‘unconcealed’ behaviours regarding the human, and perceptions of the farmed nonhuman . Therefore placing my work beyond a linear concept of past/present/future and exploring the idea that we are in the future/present/past at any point in perception.

Focusing on the Museum itself is a starting point for future world building – what kind of world does the Museum exist in? How do people live? What values and beliefs do they hold? What values does the Museum have, how is it organised and run? Where is it? What does the building look like – if it is in a building? Where is it? If in London – what does London Look like? Who organises the Museum? Are they Human? How did the world change from the past to this future world? What caused the changes? When were they?

Such questions lead to artworks that clarify these questions – for example, an interview with the Museum Director, making a model of the physical museum, making a banner that was carried in peace marches urshering in the new era, interview with people on the marches. Alongside this Utopian world- building, archival works are/will be developed to remember the past /present). These works make our present world ‘strange’ or ‘defamiliarise’ it. For example artworks that focus on specific organisational and value systems -the education system, the food system, the family kitchen, the thought system that allowed humans to think it was accepable to kill, skin and use another beings for a handbag.

The works are being developed haphazardly at the start of the research – responding to opportunities to show work, alongside other artists and in specific galleries e.g. the handbag factory in London. I have confidence they will build to a coherent collection. This virtual web site is also under construction.

‘Remaking time’, as an aspect of Fictioning, will be a central preoccupation for this research. For example, I am currently exploring how I can write chapters on Museums and on Biocapitalism, from the future perspective of the Museum of Human Violence in 2064.

Part of the decision to focus on violent discourse to non-human animals stems from the fact that for most of my life I have colluded in this cruelty. I come from generations of dairy/sheep farmers and grew up on a farm in the North of England. Like most people, I was taught that it is not only normal but necessary to eat and use other animals. Along with this belief comes dissociation: the deadening of empathy toward the suffering of others. I have come to understand that this fundamental violence to the non-human animal is, while primarily to end the suffering of the non-human, also necessary as a first step in ending all human violence. Dawson (2015:11) reminds us of what Derrida had to say about ‘this ontological and linguistic violence’ that reduces what he calls:

… the heterogeneous multiplicity of the living” to a singular Other: the animal. Such efforts to demarcate the human have been central to a range of historical atrocities, from the legal, medical, political, and economic efforts to differentiate species that characterized slavery and colonialism to contemporary manifestations of racial and species hierarchy in industrial slaughterhouses in the rural US. To disrupt such forms of human-animal dichotomy is to challenge some of the fundamental cultural logics of modernity and empire, which render other beings killable, or at least exploitable, without the need for ethical reflection.

As a final note on method: I notice my artistic practice is developing in a satisfying synergy with my reading and writing which is leading to a waterfall of possibilities. I am finding first-hand how making and reading, and their corollaries, feeling/experiencing and thinking are leading to knowledge-building in ways I have not previously encountered when my research was only focused on talking and thinking (ie no making involved) .

- I make A. It leads to reading B

- B leads me to make C

- A also leads me to make D

- B, and C, lead me to read E

- D leads me to read F

- D also leads me to make E

- E and F leads me to read G

- D, E, F. G. combined lead me to make H and I…………………………

A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H and I are leading to me building new knowledge that is Grounded Theory: based in inductive reasoning, rather than knowledge from starting with a hypothesis that I am testing out (ie my visual utopian experimentation is creatively open-ended rather than a pre-designed to prove or text a theory involving eliminating bias, collecting and analysing data).

References

Abensour, M. (1999) ‘William Morris and the Politics of Romance’, in Max Blechman (ed.) Revolutionary Romanticism, San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Avani Ashtekar (2022). https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2022/07/15/book-review-experiments-in-imagining-otherwise-by-lola-olufemi/. (Accessed 1 March 2023)

Braidotti, R. (2021) Posthuman Feminism. Cambridge: Polity Books.

O’Sullivan’s (2016)

Brettkelly-Chalmers, K. (2019) Time, Duration and Change in Contemporary Art.

Burrows, D. and O’Sullivan, S. (2019). Fictioning. Edinburgh University Press.

Castells, M. (2010a). The rise of the network society: The information age—Economy, society and culture (Vol. 1, 2nd ed.). Wiley.

Coleman, R., & Lyon, D. (2023). Recalibrating everyday futures during the COVID-19 pandemic: Futures fissured, on standby and reset in mass observation responses. Sociology, 57(2), 421–437.

Cronin, J. Keri and Kramer, Lisa, A. (2018). Challenging the Iconography of Oppression in Marketing: Confronting Speciesism Through Art and Visual Culture, in Journal of Animal Ethics, Vol. 8, No. 1 (spring) pp. 80-92.

Dawson, A. (2015) Dawson, A. (2015). Biocapitalism and Culture. paper presented at the Environments and Societies colloquium on March 4. Available here: http://environmentsandsocieties.ucdavis.edu/files/2015/02/Dawson_Biocapitalism-Culture.pdf

Deckner, K. (2019). Exploring “Heterochronias”. In: Hartmann, M., Prommer, E., Deckner, K., Görland, S. (eds) Mediated Time. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24950-2_5

Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 2. 19 Derrida, 31.

Floridi, L. (2010). Information: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. Floridi, L. (2013). The ethics of information. Oxford University Press.

Jennifer Johung (2016)Speculative Life: Art, Synthetic Biology and Blueprints for the Unknown. Theory, culture and society. Vol. 33. (3) 175-188.

Kate Brettkelly-Chalmers, (2019). Time, Duration and Change in Contemporary Art: Beyond the Clock. Published by: Intellect https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv36xvwqb

Earle, J. (2019) Imagining Otherwise: The Importance of Speculative Fiction to New Social Justice Imaginaries. page 3. in Catalyst: Feminism, theory, technoscience. No 5 (1).

Groys, B. (2009) Politics of Installation. E-flux journal. January. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/02/68504/politics-of-installation/(last accessed 10 August 2023).

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene.

Kester, G. H. (2010). Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. USA: University of California Press.

Lee, D. (2018). Can humans survive a faster future? The RAND blog, 1 May 2018. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/blog/ articles/2018/05/can-humans-survive-a-faster-future

Levitas, R. (2017). Where there is no vision, the people perish: a utopian ethic for a transformed future. Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity. cusp.ac.uk/essay/m1-5

Olufemi, L. (2021). Experiments in Imagining Otherwise, London: Hajar Press.

Preciado, 2014). Heterochronia’s. https://www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2017/03/heterochronia/#:~:text=Michel%20Foucault%20borrowed%20the%20term%20“heterochronie”%20from%20the,time%20and%20its%20relationship%20with%20hegemonic%20historical%20narratives

Romanow, E. (2013). Aesthetics of defamiliarisation in Heidegger, Duchamp and Ponge. Unpublished PhD thesis. Stamford University.

Seitz, Sergej. (2022) “Affirmative Refusals: Reclaiming Political Imagination with Bonnie Honig and Lola Olufemi.” Genealogy+Critique 8, no. 1 (2022): 1–22. DOI: https:/doi.org/10.16995/gc.9942

Sharma, S. (2014a). In the meantime—Temporality and cultural politics. Duke University Press.

Mason, T., & Bawden, D. (2023). Times new plural: The multiple temporalities of contemporary life and the infosphere. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 1–11. https:// doi.org/10.1002/asi.24812 MASON and BAWDEN 11 23301643, 0, Downloaded from https://asistdl.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/asi.24812 by City University Of London Library, Wiley Online Library on [06/07/2023].

Viktor Shklovsky, “Art as Device” in Theory of Prose, translated by Benjamin Sher, (Dalkey Archive Press, 1990, ISBN 0916583643)

O’Sullivan, S. (2016). Deleuze against control: fictioning to myth-science. In Theory, Culture and Society. Vol. 33. Issue 7-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276416645154

Savolainen, R. (2006). Time as a context of information seeking. Library & Information Science Research, 28(1), 110–127.

Statkiewicz, M. (2009). Rhapsody of Philosophy: Dialogues with Plato in contemporary thought. PA: Pennsylvania State University.