This article is partly a response to the fact of The Museum of Human Violence being housed in what was, before the Giant Rupture, the Tate Modern Contemporary Art Gallery. The choice to house the Museum of Human Violence in this iconic building, once a power station, was largely owing to it being empty at the time of the Museum’s inception; being large, famous, in central London, and previously being a museum, of a kind.

Added to these positive reasons for the building’s new role, is the question of how the Tate as an institution was responding, pre Rupture to challenges related to historic inequalities, diversity, colonisation, abuses and lack of representation. This article considers some of these challenges to museums pre-Rupture, and draws on archival material from a small case study, conducted in November 2024 at the Tate Britain to illustrate responses to violence to the nonhuman evident on that date.

An anecdotal and opportunistic case study is used to raise some issues about institutional response to violence pre-Rupture. This is based on one person’s experience and observation. It is not in any way representative. Nevertheless it offers some useful insights. This writing touches on ideas being discussed in the early part of the century relating to decolonising Museums, the role of museums, as well as institutional critique. The article starts with the case study, with little commentary, and moves on to a discussion, incorporating writing from the time about decolonising museums and institutional critique.

The evidence presented is used to conclude that while the Tate Britain, as an example of art institutions at the time, was making attempts to show artworks that were by artists from marginalised groups in society at the time, these mainly focused on sharing marginalised experiences. It is clear that it was important for these experiences to be shared, but that underpinning questions about capitalism, anthropocentrism, human violence and colonisation of the nonhuman and the land, as well as questions about what it meant to be human in the early 21st century were largely ignored.

Furthermore there is some evidence that some artists themselves, as well as the institution as a whole, ignored the intersectionality of violence by presenting works from a human perspective that directly involved violence to other animals and other nature generally.

The Case Study

The writer’s visit to the Tate Britain 40 years ago toward the end of 2024 was soley for the purpose of seeing the work of the Nominees for the Turner Contemporary Art Prize that year. This prize was well established and prestigious in Britain at the time, and was for a British artist whose work encapsulated ‘the best’ and ‘the new’ in contemporary art at the time. The author did not research the prize nominees beforehand, and nor did they research other work being shown at the Tate. It seemed apparent that the judges for the prize had chosen artists who had in common a focus on experience as a member of a minority community in Britain: Pio Abad grew up in the Philippines and their work included sculptures and drawings of artefacts from an Oxford museum to reflect on colonial and overlooked human histories. Claudette Johnson was a founding member of the Black British Art Movement and was known for their large paintings of black subjects that countered the marginalisation of Black people in European art history. Jasmina Kaur grew up in the Sikh community of Glasgow and showed eclectic, largely found, objects to reflect on their upbringing in that community. Delaine Le Bas made an immersive installation to reflect on their cultural memories as a Roma-traveller. In summary it appeared that ‘identity’ was a prevailing theme.

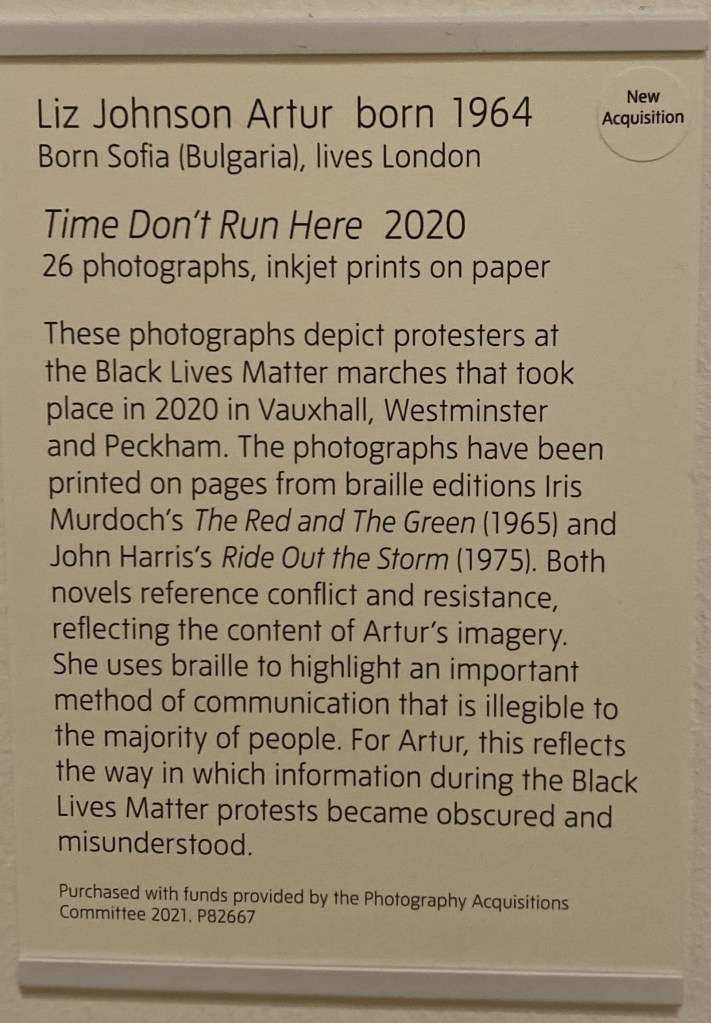

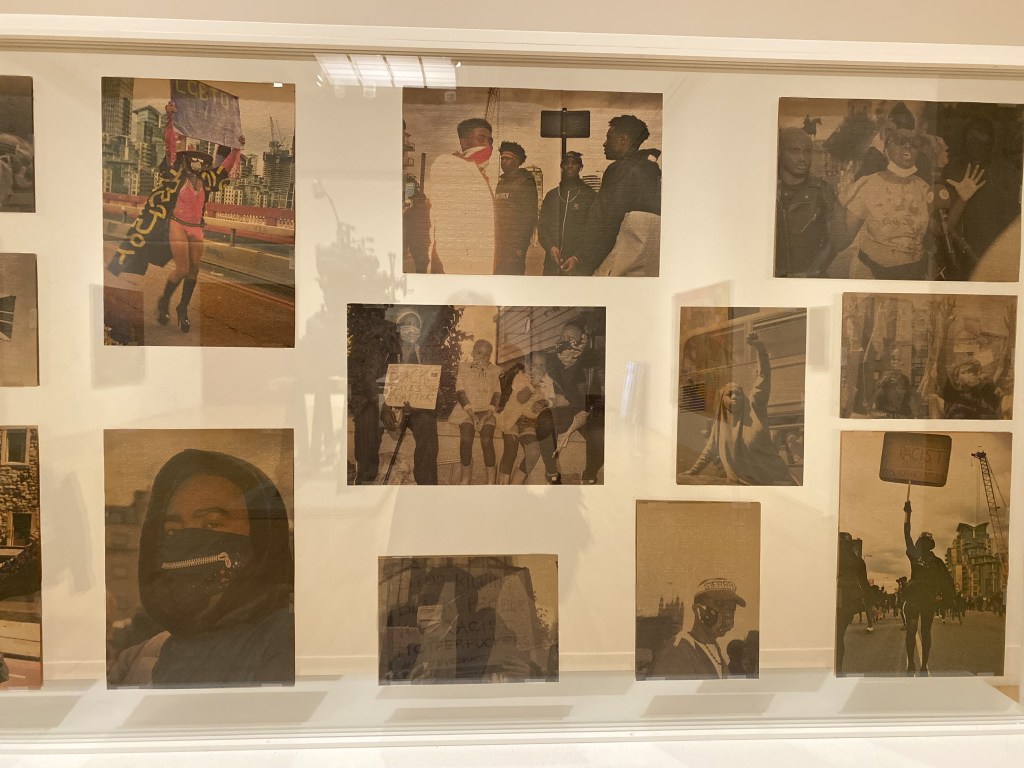

It seems that each artist nominated for the prize drew on the history of marginalisation and exclusion, and in three cases, migration from parts of the world that were colonised and exploited by Europeans. Abad touched on kidnap of a Prince of the Philippines, and Johnson depicted the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in the USA, whose death directly lead to the Black Lives Matter protests in the early 2020’s – photographs of which were shown in a different unrelated Museum gallery. The work of Le Bas and Kaur focuses on their culture. Perhaps all this work included aspect of what can best be described as ‘identity art’ : that is as showing the characteristics, beliefs and values that define an individual or group. In the early 2000’s it seems that showing identity art was a common institutional response to charges of racism, bias and colonisation. It was believed that showing aspects of the lives of varied groups in society would allow the viewer to gain new perspectives and understanding of ‘other people’s’ lives. Perhaps it was thought too, that ‘others’ had been silenced for long enough and it was time they were ‘allowed’/encouraged to speak. (This can be related to discussions of epistemic violence in the 30 or so years leading up to this time: Spivak, 1988. Spivak wrote about silencing of the knowledge of the less powerful, colonised and ‘othered’). In the case of this historic show in the Tate Britain in 2024, it might also have been that the judges were thinking about the audiences that typically went to the large central city galleries in those days to see Art: largely white and middle class. Presumably it was hoped that works that spoke to the experiences of cultural minorities would bring a more diverse audience to the Gallery. We do not know if that was actually the case. Showing the lives of ‘others’ to create greater understanding might also be questioned from our stance today: we might go further and question whether this is patronising – given that it assumes that those lives being ‘shown’ belong to a class of people who did not visit the museum in great numbers (white working class identity art was not apparent on this visit).

The work of Abad did include some direct reference to colonisation for example the reference to a kidnapped Prince who was ‘captured’ and shipped to Europe after his mother was murdered – the engraved marble hand on show reached back to mother and home. However in this work while the violence of the colonisers was foregrounded, the violence of the (presumed ceremonial) swords that were displayed goes unremarked.

This work selected for the Turner Prize in 2024 made little reference to the catastrophic events of the 2020’s: war and genocide in many parts of the world, including Gaza, Lebanon and Sudan; catastrophic migration and refugee crises – much caused by global warming as well as internal conflict; slaughter and torture of nonhumans on an unprecedented scale; mass consumerism; addictions to drugs and other substances in the developed world; poverty and starvation of millions of people in the exploited worlds; global warming and plasticisation of the seas. Looking back at this pre-Rupture world of chaos, this snapshot of the most prestigious contemporary art of the time seems strangely out of kilter – especially since it appeared initially, through choice of these four artists, a direct institutional response to issues relating to marginalisation and by association, injustice.

The Duvet Gallery

To reach the Turner Prize nominations the writer needed to cross the Duveen Gallery. Here was a large installation by Alvaro Barrington: a Venezuelan artist who lived in London in the early 21st century. The instillation was called, ‘Grace’ and Barrington wrote: ‘Grace is the constant reimagining of Black culture and aspirational attitude under foreign conditions. GRACE here explores how my grandmother, my mother, and my sister in the British Caribbean community showed up gracefully.’ This exhibition was perhaps on the margins between identity art and a more political framing of the institutional exploitation and oppression that existed at that time in the British Caribbean.

On the author’s journey out of the gallery they passed through/past other galleries and paused to snap works that caught their eye because they directly were about violence or violence was involved in some way. Or because of their more overtly political stance. For example, next door to the Barrington show and the Turner prize artists was a temporary exhibition of contemporary art:

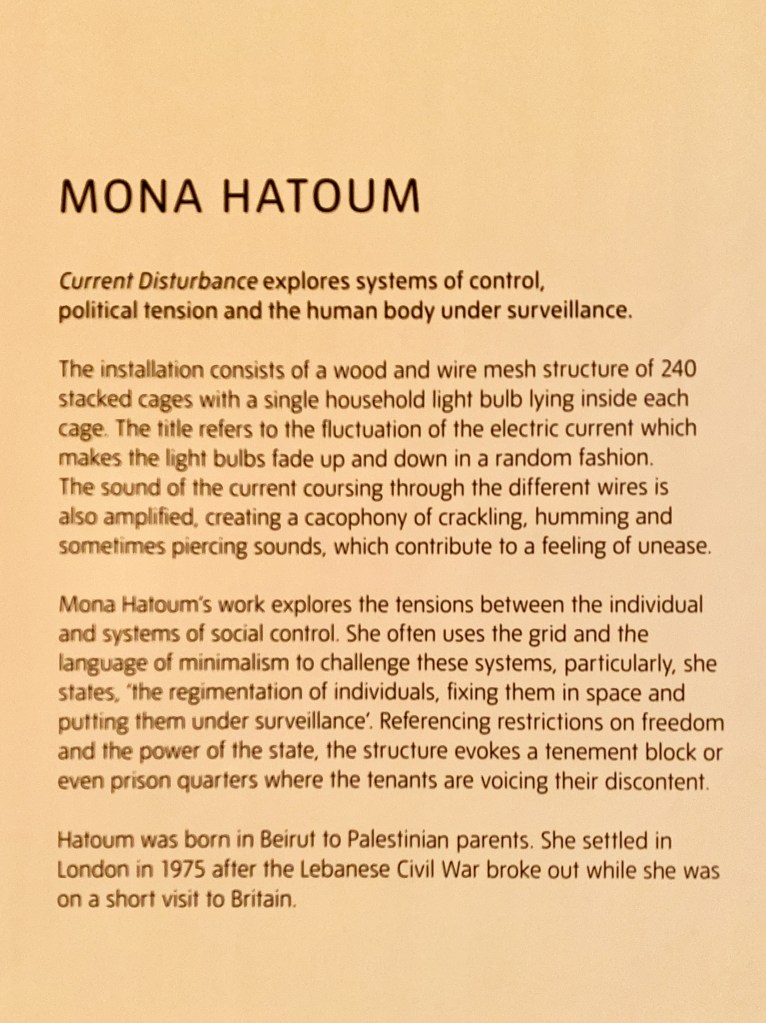

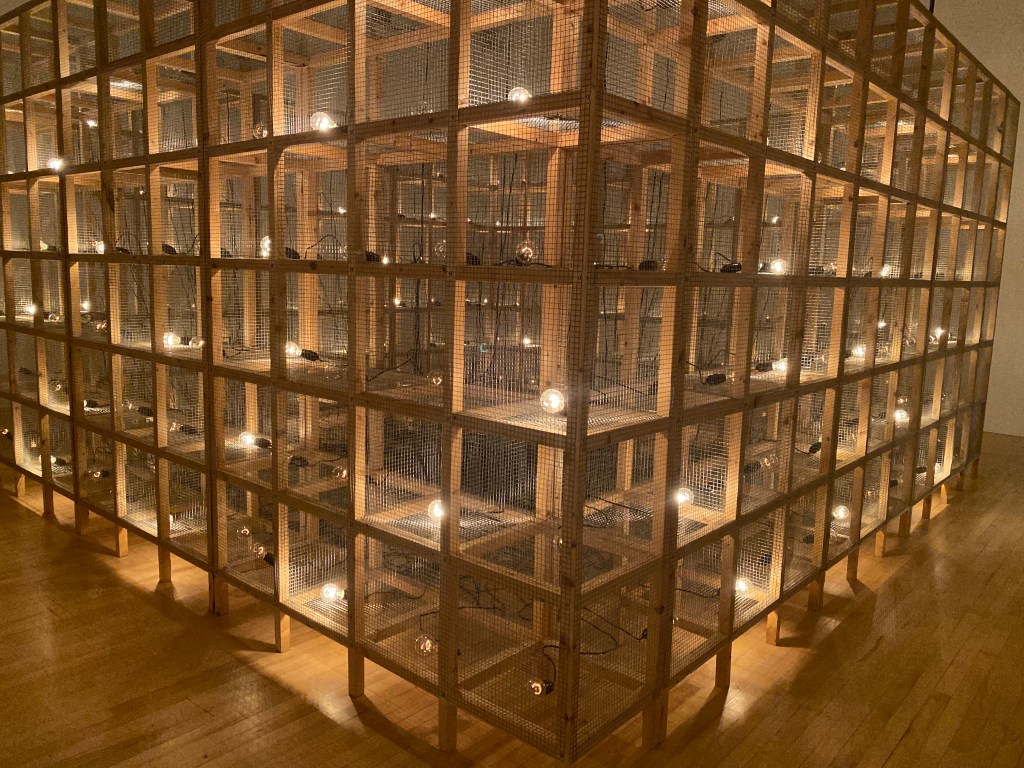

The writer was also intrigued by the overtly political work of Mona Hatoum, an artist of Palestinian heritage, then living in London. Hatoum explored systems of social control including surveillance.

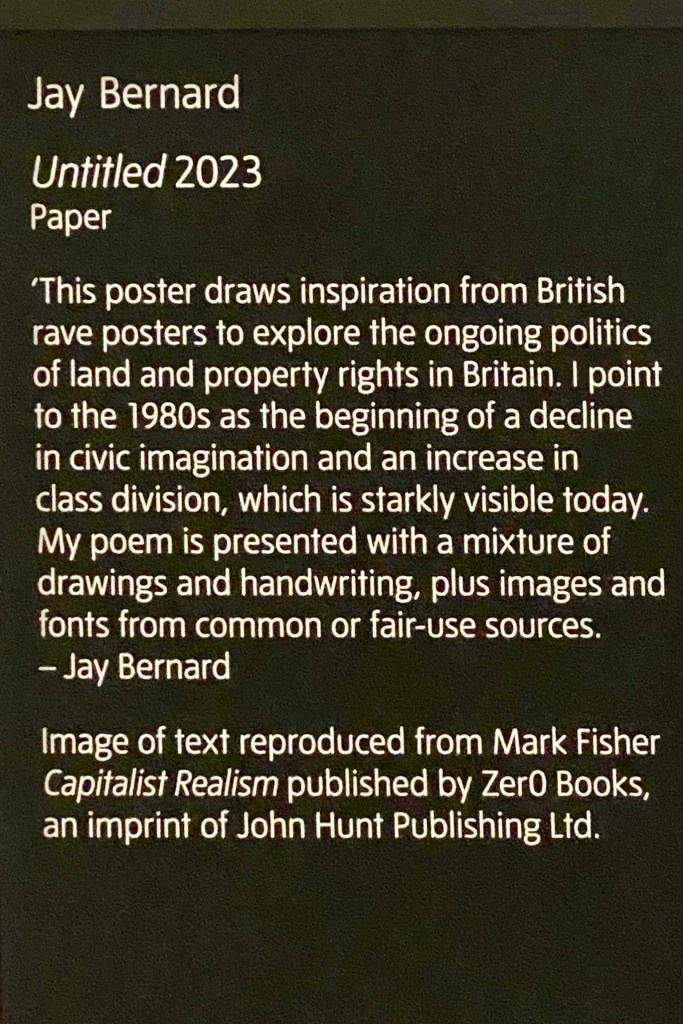

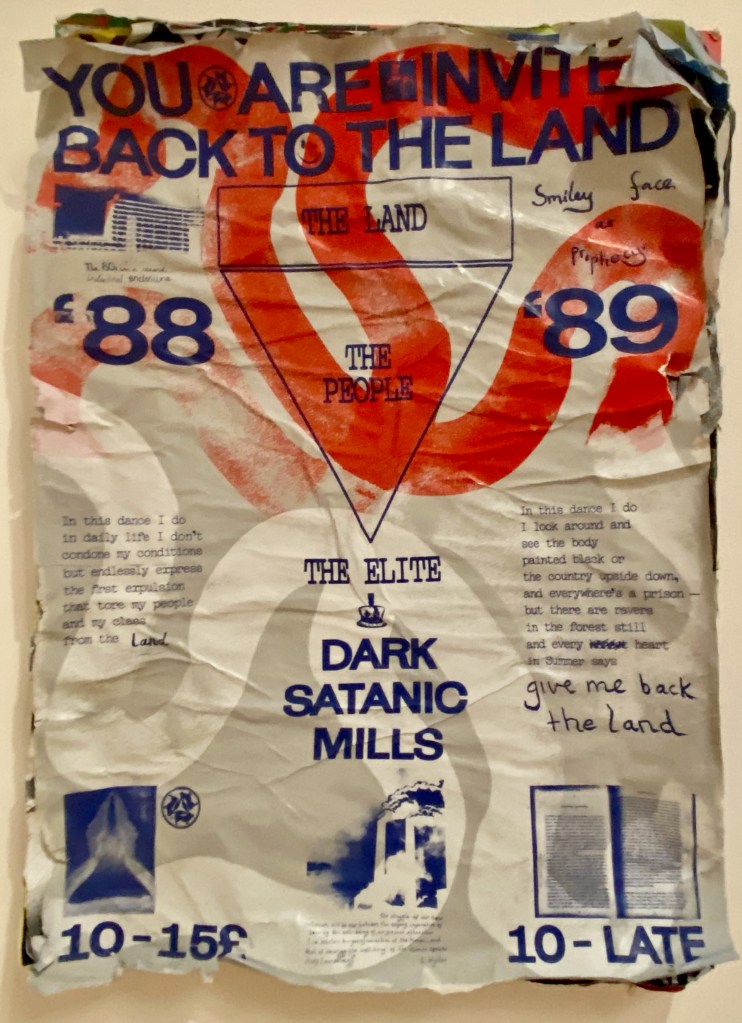

And in the permanent collection the writer found this overtly political poster that class division – land and property rights: a rare example of work that highlights exploitation of the working classes in Britain.

Representation of the nonhuman in the Museum

At the end of November 2024 the Tate Britain seemed unaware and unconscious of the intersectionality of violence and oppression. The writer found no examples of works that specifically highlighted the plight of farmed nonhumans or of hunted wildlife, or generally of the colonisation of the nonhuman. On the contrary where nonhumans were specifically referenced there seemed to be an almost deliberate avoidance of mention of cruelty, implicit or explicit, toward them. In two cases reference to the nonhuman were used without mention to draw attention to gendered violence and racism, with no apparent understanding of the intersectionality of violence by either artist or institution. In two cases also, the parts of murdered nonhumans were used as a normalising device for this violence.

Case 1. Rex Whisper and ‘The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meat 1926-7)

The original Whistler mural was commissioned in 1926 as “decoration for the new refreshment room” in the Tate Modern. It took Whistler 18 months to complete when he was a 21-year-old artist who’d recently graduated from the Slade Art School. The mural was closed to the public in 2020 because of its depiction of a black child being taken into slavery, with his mother, naked, up a tree and stereotypical images of Chinese people. However in 2024 it reopened to include a 20 minute video, Viva Voci, commissioned from Keith Piper, a black British artist, in which a fictional academic, professor shepherd, interrogated Whistler about his work and in which they also discussed Whistler’s social circle and the ‘bright young people’ hung out at the Gargoyle Club where black musicians played during the Jazz Age.

This attempt by the Tate Modern to interrogate the artist, was, it seems, in response to allegations that the mural was racist. From our perspective now, this clumsy attempt seems ludicrous on a number of levels. Firstly it totally ignores that any artwork is made in a specific context and has to be read in that context. Perhaps a note to the effect that society in 1926 was overtly racist might have been sufficient. Additionally, while clumsily attempting at least to point out racism, the re-presented/re-contextualised mural remains species in the extreme. And no mention of this fact is made. The whole point of the mural is to hunt and kill nonhumans. By not addressing this fact, the Tate Britain colluded in and normalised this violence.

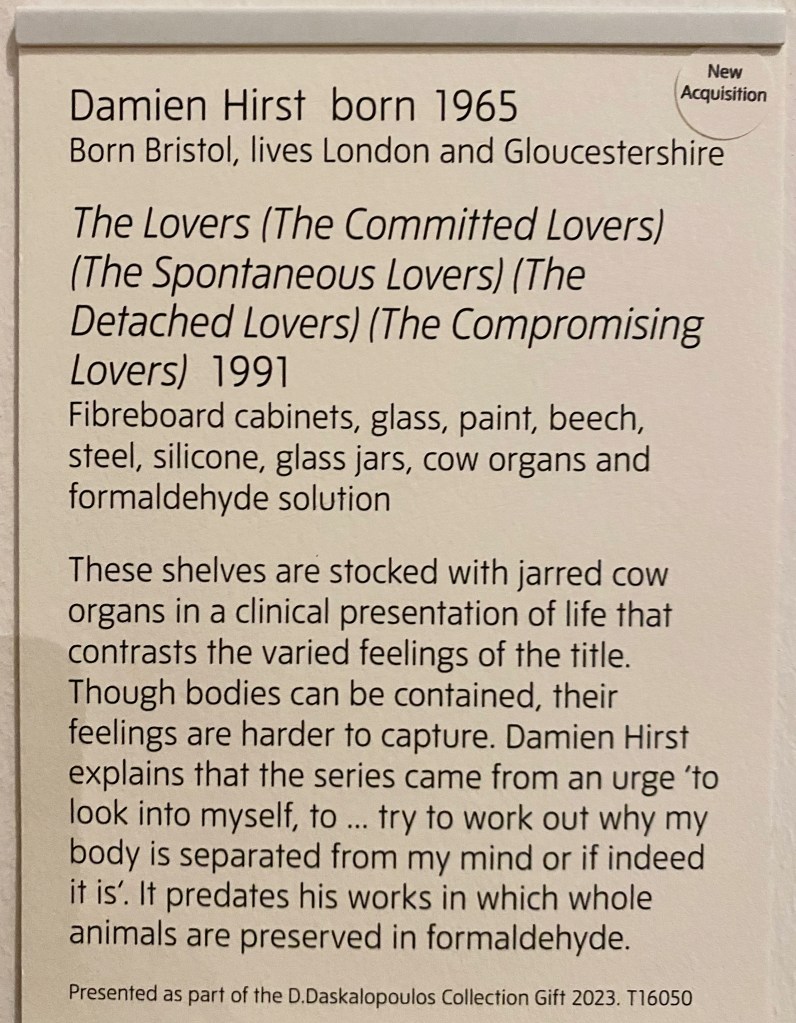

Case 2: Damien Hirst. ‘the Lovers’ and ‘Formaldehyde Sheep’.

The shockingness of the violence here is hard to stomach. These displays of murdered nonhumans and their parts, with no commentary from either Hirst or the Tate Britain is evidence above all, of the normalisation of violence to the nonhuman in the mid-2020s. Such institutional violence is in stark contrast to the attempts seen above to address violence to marginalised humans. (although thank goodness that violence was never portrayed in such stark and ugly ways in UK art galleries). The violence to the sheep and cows in the displays above is highlighted by Hirst’s apparent comments that this work explores himself – why his body is separate from his mind, if indeed it is. Violence on this scale with a purpose to explore an unanswerable question about oneself seems incomprehensible, and savage, for our perspective in 2065.

Case 3: Wermer. The Violet Revs. 2016

Again, animal parts are used to normalise violence to the nonhuman and to make a point about a different inequality – in this case gender inequality. (I am tempted here to leave out the N in the title of the work). In the information accompanying the work we are told that faux fur and second-hand fox tails are used – as if the fact of ‘second-hand’ masks the violent way in which these nonhumans died.

Again violence against the nonhuman is used without comment by the Artist or by the Institution, and because of this, violence to the nonhuman is again condoned, normalised and, importantly, invisible. We are led to the conclusion that violence to the nonhuman in pre Rupture art galleries/museums did not matter .

Discussion

Before the Rupture of 2034-36 there is evidence that museums and art galleries were working to address the white, ethnocentric, colonising history of displays in the art galleries and museums of Europe and the USA. This was particularly evident in the first 30 years of the 21st century. In this brief, and necessarily inadequate look at some of these attempts at the Tate Britain in London, it is apparent that such endeavours, while necessary and worthwhile in some ways, in others totally failed to recognise the inter-relationship between different forms of oppression; and because of this ignored, colluded in, and promoted violence to nonhumans.

Discussing this blindness to some oppressions or challenging some oppressions at the cost of supporting others raises the status of institutional critique in the first quarter of the 21st century. Institutional critique had become, from Andrea Fraser’s perspective (2005) institutionalised since first rearing up as a challenge to the Museums in the 1970s. While Institutional critique was recognised as important by the Institutions, Fraser claims that the critical claims associated with it were dismissed. The claims included …. Fraser attributes this to the corporate control of the museums finances and the global art market. Institutional critique criticised art as an institution, including the institution in which art was shown, but also studio art practices: as Fraser (2005) points out any critical intervention will always be historically specific and its effectiveness will be limited to a particular time and place.

An example of a critical intervention in displays of ancient human skulls and remains was reported in 2023. It involved Penn Museum in the USA in updating its policies regarding the handling of human remains. The Museum had decided to no longer put “exposed” remains on exhibition.

‘Wrapped mummies or remains enclosed in a vessel will still be considered for display with signage forewarning visitors. But all visible human tissue — such as bones, teeth, and hair — will be removed from view…It’s about prioritizing human dignity and the wishes of descendant communities,” said Penn Museum director Christopher Woods. https://whyy.org/articles/penn-museum-no-longer-display-exposed-human-remains/

This is an example of the anthropocentrism that governed institutional understanding of violence in the mid-2020s. Ancient human remains were removed, after petition, in one museum, but the remains of murdered nonhumans are shown without comment in another. Not only without comment but the fact of them once being living, sentient beings is apparently invisible. Not only this but the death of the humans on exhibit was thousands of years ago and their cause of death is largely unknown, while the deaths of the nonhumans in the Tate Britain was ongoing, on an industrial scale and everyone knew how they died – murdered by other humans.

Haacke (1974) “Artists as much as their supporters and their enemies, no matter of what ideological coloration , are unwitting partners …They participate jointly in the maintenance and/or development of the ideological makeup of their society. They work within the frame, set the frame and are being framed.”

Include reference to article below:

Also see link to museums in this article about heterochronia: https://www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2017/03/heterochronia/#:~:text=Michel%20Foucault%20borrowed%20the%20term%20“heterochronie”%20from%20the,time%20and%20its%20relationship%20with%20hegemonic%20historical%20narratives.

References

Document5

From the Critique of Institutions to an

Institution of Critique

Andrea Fraser. Artforum. New York: Sep 2005. Vol. 44, Iss. 1; pg. 278, 8

Hans Haacke, “All the Art That’s Fit to Show,” in Museums by Artists, 152.

retention time and the museum discussed in futurity paper.

also touch on memorial museums. see book on this. Memorial Museums

The Global Rush to Commemorate Atrocities

and Museums for Peace: In Search of History, Memory, and Change

Edited By Joyce Apsel, Clive Barrett, Roy Tamashiro